In Altar of Bones Lena Orlova escapes with her lover from the prison camp at Norilsk and makes her way to China on foot. Lena’s escape is based on primarily the real life stories of Clemens Forell and Slavomir Rawicz.

Clemens Forell was a German Paratrooper whose story is chronicled in As Far as My Feet Will Carry Me: The Extraordinary True Story of One Man’s Escape from a Siberian Labor Camp and His 3-Year Trek to Freedom: “In 1944 [he] was captured by the Soviets in 1944 and sentenced to twenty-five years of labor in a Siberian lead mine. In the Gulags, this was virtually a death sentence. Driven to desperation by the brutality of the prison camp, he staged a daring escape. For the next three years, Forell traveled 8,000 miles in barren, frozen wilderness, haunted by blizzards, wolves, criminals, the KGB, and the fear of recapture and retribution. Only a remarkable will to survive, and a bit of luck, allowed him to reach the safety of the Persian border. The resulting story is a rare document of the horrors faced by POWs in the Soviet Union, and a testament to the human spirit.”

Slavomir Rawicz, a cavalry officer who was captured by the Red Army in 1939 during the German-Soviet partition of Poland, made another escape against seemingly impossible odds, recounted in The Long Walk: The True Story of a Trek to Freedom: “[He] and was sent to the Siberian Gulag along with other captive Poles, Finns, Ukranians, Czechs, Greeks, and even a few English, French, and American unfortunates who had been caught up in the fighting. A year later, he and six comrades from various countries escaped from a labor camp in Yakutsk and made their way, on foot, thousands of miles south to British India, where Rawicz reenlisted in the Polish army and fought against the Germans. The Long Walk recounts that adventure, which is surely one of the most curious treks in history.”

Lena’s escape is a key sequence in Altar of Bones, but that portion of the book was cut down due to the complexity of the overall story. Here’s a glimpse of some scenes that were cut from the published book:

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Chapter Five

A full moon silvered the snow when Lena Orlova emerged from behind a tumble of boulders fifty yards down shore from the frozen waterfall. The canyons and hills around the lake were a labyrinth of caverns and tunnels, and there was always another way out, if you knew where it was.

She stood silently, her hands lightly cupping her belly. She saw what the wolves had left of the three dead soldiers, but no sign of Nikolai or the sleigh, only the tracks it had left behind. His escape from Norilsk had been a game, a way to trick her into bringing him to the secret cave, and the soldiers had been a part of it all along. Only in the end he’d betrayed them, too. He’d betrayed everyone.

He would come back later to the cave, now that he knew where the entrance was. It might be buried behind a wall of snow, but he wouldn’t let that stop him from getting back inside. Would he look for her dead bones among all the others strewn among the stalagmites and rotting caskets? Probably not. His whole heart and mind would be focused on one thing: like many before him, he thought he’d seen the altar of bones.

Well, now, he was wrong about that, wasn’t he? And the drunken madman mentioned in the Fontana dossier? He’d been wrong, as well, and Lena smiled at the thought. She hitched the sleeping roll and knapsack higher up onto her shoulder and walked away from the lake. She never looked back.

* * *

It took her five months to walk to the place where the Jenisej River flowed into Mongolia.

She walked only at night, so that her dark, fur-wrapped silhouette wouldn’t stand out against the snow-shrouded tundra. At least the nights were long, even as the winter slowly gave way to spring.

You could get a tin of tea or a bag of wheat, or sometimes a few hundred rubles, for turning in a runaway, so she avoided the scattered native villages. And although the land was locked in ice, she knew how to live off it. From her mother’s people, she’d learned how to build a snow hut and make a fire with moss scraped from the rocks and tree trunks, how to milk reindeer and snare a wild hare and fish from a hole cut in the ice.

A couple of times she spotted the smokestacks from other prison camps in the distance, but she saw no soldiers with their guns and dogs. Once, from a long way away, she heard the wail of a train whistle.

She’d thought the constant cold would be the hardest thing to endure, but instead it was the loneliness. One day, during another purga, she sat hunched in a snow hut with her bent legs drawn up under her chin and she began to talk to the babe she carried in her belly to drown out the shriek of the wind. She told her babe about the toapotror, the magic people, and about her own father who had been a Muscovite doctor, and about her own mother who’d been a witch. And about how she would be born a blessed girl child, from a proud long line, and she couldn’t be the last.

From then on Lena talked to the babe all the time. She told her all the secret things she would tell her later, when she could understand.

* * *

She sat on a grassy hill overlooking the Jenisej River, eating wild potatoes she’d dug up from a field and staring at the red poles that marked the border into Mongolia. The poles, topped by round metal signs painted with the hammer and sickle, were spaced every quarter mile or so. She’d watched for two days and nights, but hadn’t seen any patrols. She felt like the only living creature on the planet, except for the flocks of geese and ducks flying north to summer on the lakes at home.

Home.

“They say home is where the heart is,” she told the babe. “And for us that’s how it’s going to be. As long as we’re with each other, we’ll be home.”

In the end she simply walked from one side of the poles to the other, just one more step in a line of thousands she’d taken since Norilsk and the cave, one more step away from Nikolai.

She’d walked another two days down the river when she came across what she thought was an abandoned sampan. Then a shriveled old man stepped out from behind a rotting sail.

She started to run off, more out of habit than anything else, but he called after her in passable Russian. “Wait. The Reds cross over sometimes, for who’s to stop them? And there are bandits who will sell you to them for the price of a button.”

Lena turned back to him. He had the longest, thickest mustaches she’d ever seen, but his head was bald and knobby.

“Does that boat of yours float?” she asked him.

“If it didn’t I would’ve drowned long before now.”

“Will you take me downriver? I can pay you,” she added, thinking of the rubles she still had in her knapsack.

“Depends. Where are you going?”

“To Shanghai,” Lena said, pulling out of her head the only place in China she’d heard of.

The old man looked at her as if she’d just named one of Saturn’s moons. Later, when she saw a map of Asia tacked on the wall in a missionary classroom, she realized that for him Shanghai might as well have been a moon, so far away it was from his little patch of river.

* * *

The sampan man took her as far as he could, then turned her over to a great-nephew who gave her a ride on his vegetable cart as far as Uaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital and a whimsical place to Lena’s eyes, with its modern concrete buildings mixed in willy-nilly among the rows of round, felt tents the nomads called yurts. The great-nephew had a childhood friend who worked as a brakeman on the railroad and he let her ride in a boxcar all the way to Zhengzhou in China, a flat, dusty, crowded city. The brakeman had a brother . . . and so she was passed from one relative or friend to another down the length of China until, eight months after her escape from Norilsk, she found herself floating into Shanghai on a garbage scow.

She wasn’t on deck to see it, though, because the babe was coming and the pains were bad.

The family who lived on the scow feared she was dying, so they left her on the doorstep of a missionary run by French nuns known for having taken in White Russian refugees during the revolution. Sometime during the long hours of wracking labor, a woman with a pocked face and a funny-looking white paper ship on her head bent over her and shouted in butchered Russian, “Imja? Imja?”

Name? Why did they want to know the child’s name when it hadn’t even been born yet? Oh, God, had the babe died in the womb? Was she trying to give birth to a corpse?

“Katya,” she said, pulling a name out of the air, because she couldn’t think and the pain was so bad.

But after it was over and she held her daughter in her arms for the first time, she was glad she’d picked the name Katya. In the long line of Keepers, going back to the first Keeper—a blond-haired Tatar girl captured by a fierce Mongol warlord, who’d carried her off to Siberia and made her his bride—there had been many Lenas, but never a Katya, and this was a good thing. They were alone now, she and her babe, with no tribe and no past. They had only the future and each other.

The next morning, when Lena was about to put little Katya to her breast, the nun with the pocked face burst into her room.

“Get up! Get up! We must hide.”

“Why?” Lena cried, although her finely honed instinct for self-preservation already had her out of the bed, with the babe clutched tightly to her chest. Her legs felt like the wet noodles they’d been feeding her.

“Don’t you hear it?” the nun said, tossing Lena a quilted robe. “Quickly, quickly now . . . ”

To Lena, the teeming city outside the windows of the mission was a constant cacophony of noise, but now she heard it too. Gunfire, and screams.

“The Japanese have come, and may God have mercy on our souls—they’re killing everyone.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________

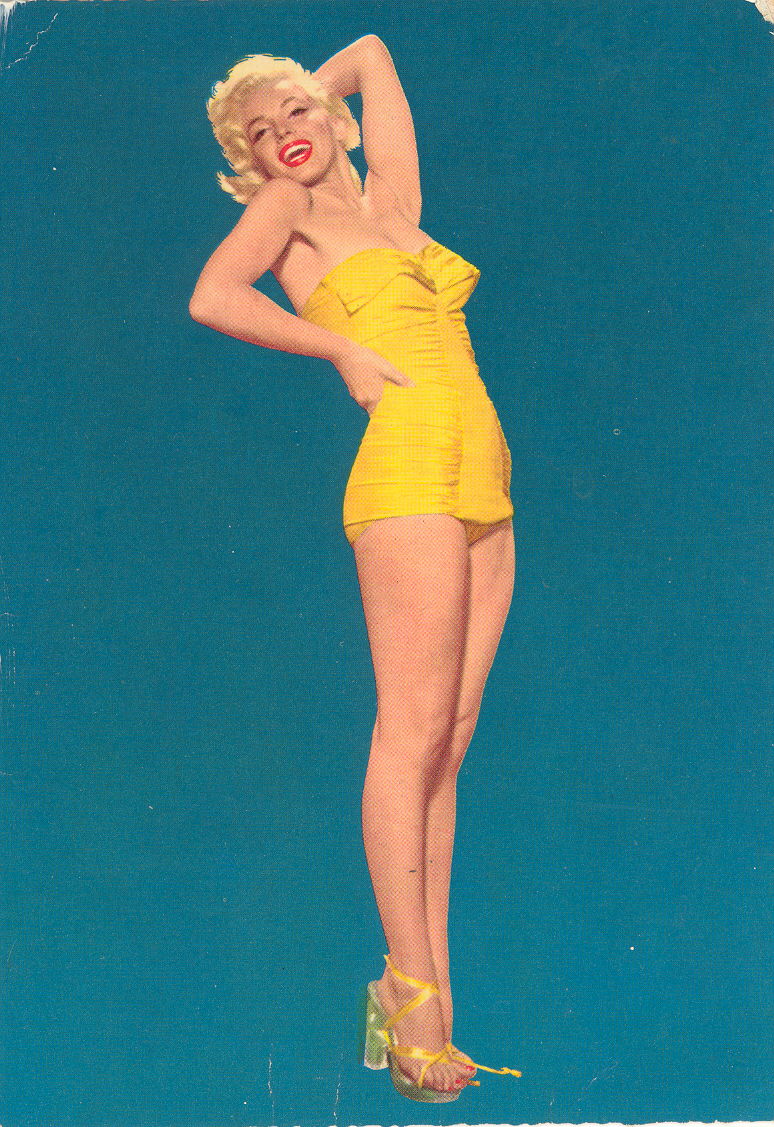

Be sure to check back next week for a behind-the-scenes look at Marilyn Monroe’s role in Altar of Bones.

The flashback scenes with Marilyn Monroe in Altar of Bones are some of my favorite I’ve ever written. Many of Marilyn’s lines in the book are things she actually said. Here are some more memorable quotes from her:

The flashback scenes with Marilyn Monroe in Altar of Bones are some of my favorite I’ve ever written. Many of Marilyn’s lines in the book are things she actually said. Here are some more memorable quotes from her:

Posted by philipcarter

Posted by philipcarter

The original coroner’s report ruled that Marilyn Monroe committed suicide, but there is enough mystery still surrounding her death that it could have been suicide, accidental overdose, or perhaps even murder. In

The original coroner’s report ruled that Marilyn Monroe committed suicide, but there is enough mystery still surrounding her death that it could have been suicide, accidental overdose, or perhaps even murder. In